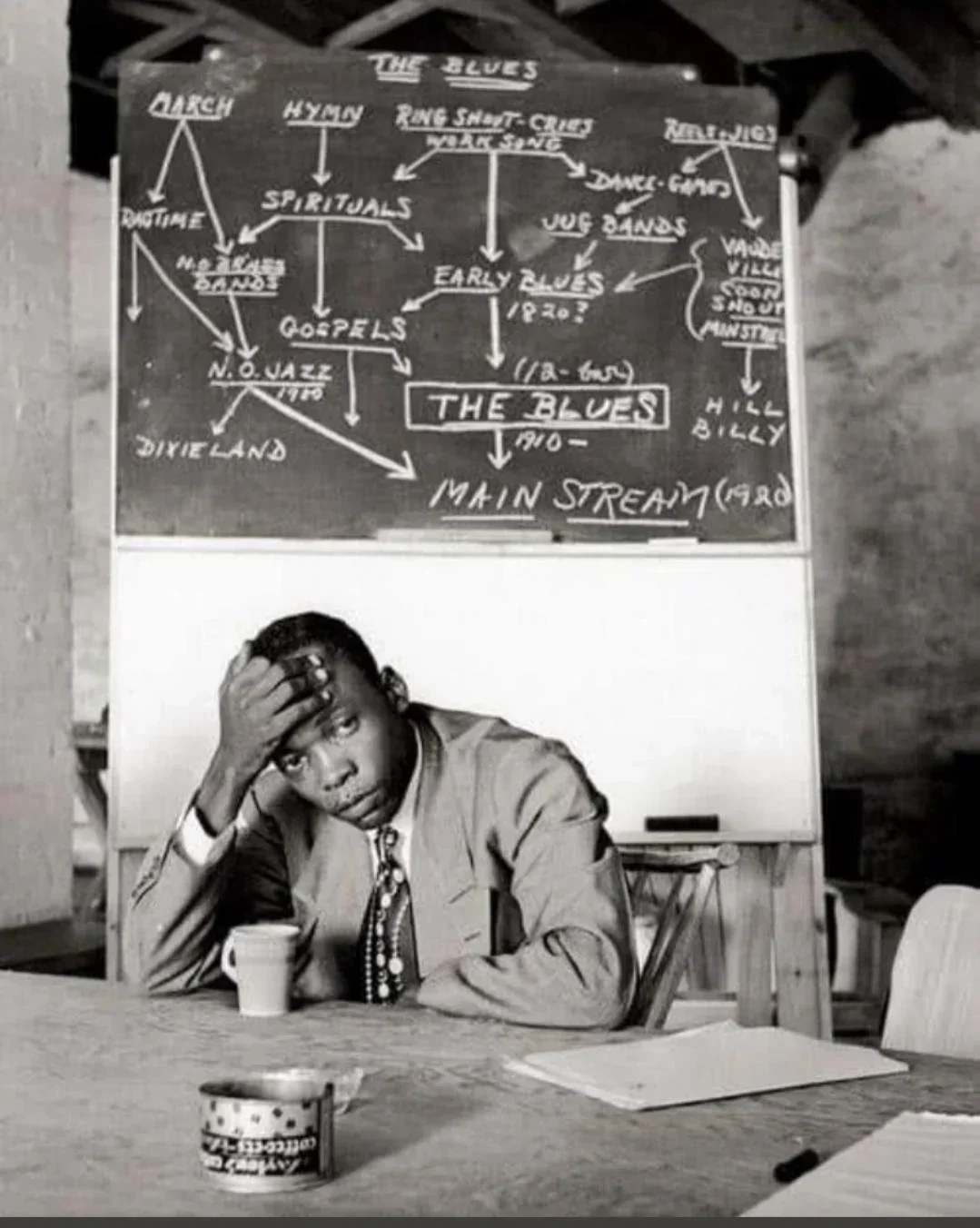

Why Gospel, Jazz, + The Blues Must Be a Core Requirement to Contemporary American Music Education

If you love R&B, rock, pop, musical theater, or hip-hop, you’re already carrying gospel, jazz, and blues in your ears. The question is: do you know their story?

I learned early on that you study the world when you study music. You study history and politics, religion and philosophy, science and art. You study people, their stories, and the ways they endure. What a glorious lesson and the essence of The Sacred Voice. It’s why I believe the study of music is always more than the study of scales, repertoires, or technical proficiency - it is the study of lineage and truth.

This conviction surfaced again in a recent faculty meeting. Our department gathered to discuss revisions to our curriculum, particularly around which vocal courses should be required and which could remain electives. The discussion landed on gospel, blues, and jazz performance courses. The answer seemed pretty straightforward for most of my colleagues: any courses involving jazz, gospel, and the blues need to be mandatory for any student who wants to study American contemporary music.

Not everyone agreed. A colleague, whose training had been almost entirely within the walls of the very school where we teach, remarked: “Gospel should be an elective because of its ties to Christianity.” The comment stung. My immediate thought was that this revealed a fundamental misunderstanding - not only of gospel, but of contemporary American music itself. Our music college is not a seminary: no one’s teaching theology. We’re teaching music theory, cultural heritage, history, and performance practices that underpin virtually every genre our students aspire to.

That moment also revealed something deeper. His comment wasn’t just one person’s opinion - it was an echo of what happens when gospel is treated as an elective at a contemporary music school. I found myself asking SO many questions - what is he teaching his students about American music history? Despite the religious undertones, does he know what gospel music is in contrast to jazz and the blues? Had he ever taken a gospel course himself? If so, who taught it, and how was it taught? What narratives and techniques were included and (more tellingly), what was left out? The absence of required study spawns precisely this kind of confusion.

By contrast, my own training always seemed expansive. From my childhood Sundays in church pews, through the classrooms of elementary and high school, into community colleges and universities where I studied classical voice and opera, and into sacred spaces and community gatherings around the world, the message was consistent: when you study the arts, you study the whole world. You study how people survive, how they rejoice, and how they protest. The final result is art. So, to make gospel, jazz, and blues electives is to weaken the holistic capacity of American music education. It strips education down to technique without heritage and performance without reference. That is exactly why these traditions must remain central in any contemporary American music curriculum.

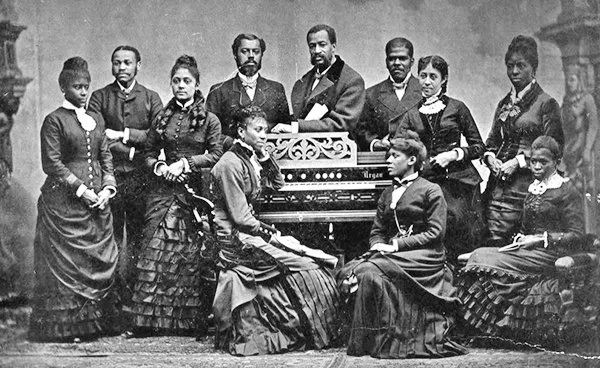

The National Museum of African American History and Culture states it plainly: “African American spirituals, gospel, the blues, and jazz are among the most influential on the development of American music” [NMAAHC, 2016]. Without them, the soundtrack of the 20th and 21st centuries would not exist.

The blues taught us the twelve-bar format, “blue notes,” and the lexicon of sadness and survival. Rock, R&B, and country elevated the structure.

Jazz gave us improvisation as the centerpiece of creativity, swing sensibility, and harmonic daring. Its influence pulses through hip-hop sampling, neo-soul harmonies, and pop balladry.

Gospel passed on melisma, call-and-response, complex harmonies, and the deep relationship between song and community identity. Modern vocal style as we know it would scarcely exist without gospel.

Music historian Eileen Southern summed it up succinctly: “Without the spirituals there would have been no gospel songs, and without gospel, there would have been no rhythm and blues. Without rhythm and blues, there would have been no rock and roll” [Southern, 1997]. This is not exaggeration - it is genealogy. To reduce gospel to an elective in a contemporary American music school because of its religious origins is to commit an injustice against both cultural and musical heritage. Gospel is more than religious doctrine - it is an historic and cultural force. Ethnomusicologist Mellonee Burnim underscores this: “Gospel music cannot be reduced to mere religious practice; it is both sacred and secular, a vehicle of community identity and cultural expression” [Burnim, 2006]. Consider gospel’s impact across generations:

Aretha Franklin: infused gospel’s fire into soul and R&B.

Whitney Houston: carried gospel’s soaring power into every vocal peak.

Beyoncé: draws upon gospel melismas and harmonies in ballads and live performances.

Naturally, gospel’s influence extends far beyond Black American vocalists:

Elvis Presley grew up in gospel quartets and Black church services. He once reflected: “We do two shows a night for five weeks. A lot of times we’ll go upstairs and sing until daylight - gospel songs. We grew up with it… it more or less puts your mind at ease. It does mine.” His phrasing and emotional delivery carried gospel directly into rock and roll.

Jerry Lee Lewis translated Pentecostal revival energy into pounding piano and ecstatic vocals.

The Rolling Stones leaned heavily on gospel aesthetics. “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” opens with a choir steeped in gospel tradition, and Mick Jagger often commanded audiences like a preacher leading a congregation.

Bruce Springsteen staged concerts that resembled secular tent revivals, with gospel choirs and communal choruses defining songs like “Land of Hope and Dreams.”

Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” is essentially a gospel ballad at its core.

Adele’s “Someone Like You” showcases melismas drawn DIRECTLY from gospel practice.

Coldplay’s “Fix You” climaxes in communal chorusing that echoes gospel harmonies.

This is why gospel, jazz, and blues cannot be confined to electives—they live at the very heart of the American sound. In 2014, I was hired to sing with the East Coast Inspirational Singers, a New York–based gospel choir contracted to perform alongside major recording artists such as Patti LaBelle and Josh Groban. That experience made clear to me how gospel functions not only as a sacred tradition but also as a professional and cultural cornerstone that even the biggest names in popular music rely upon to bring depth, authenticity, and power to their performances. Ethical music study demands that we acknowledge this kind of context. Learning Beethoven means learning the Enlightenment. Learning Stravinsky means grappling with World War I and modernism. Learning contemporary American music means studying the Black experience that birthed gospel, jazz, and blues. It means tracing the songs of enslaved Africans that became spirituals, the field hollers that became the blues, the improvisers who redefined freedom through jazz, and the gospel singers who testified for entire cultures through tyranny and triumph. Musicologist Guthrie Ramsey captures it well: “African American music is the mirror of the social and cultural history of its people, a soundtrack of survival and creativity in the face of oppression” [Ramsey, 2003] To exclude gospel from core study is nothing short of erasure. It signals to students that they can perform genres without engaging with their roots - that Black creativity is optional.

Music is never “just notes.” It is:

Science: acoustics, resonance, the physiology of the voice.

Math: rhythm, harmony, formal structures.

Art: improvisation, beauty, and aesthetic choice.

Humanities: history, philosophy, and literature.

Religion: shaping worship and community through sound.

Politics: protest, resistance, and identity forged in song.

Blues was conceived under Jim Crow segregation. Jazz flourished in the Harlem Renaissance. Gospel fueled social movements and sustained spiritual fortitude. Angela Davis reminds us: “Black women’s blues and gospel music articulate a collective memory, a cultural history of resistance, and an insistence on self-definition” [Davis, 1999]. That is integrity in music education: understanding music as science, politics, history, and soul combined.

Some colleagues argue: “Why not let students choose? If they want gospel, they’ll take it.” But curriculum has signal value. It tells students what their institution deems vital. Electives are options. Core is required. The majority of contemporary music students want to perform R&B, hip-hop, pop, soul, and rock - all genres rooted in gospel, jazz, and blues. To frame those roots as optional is both superficial and misleading.

Cornel West puts it bluntly: “You can’t talk about American music without talking about Black music. You can’t talk about American democracy without talking about Black struggle” [West, 1999]. Making gospel elective implies that Black struggle, creativity, and sound are themselves elective. That is unacceptable. When we exclude gospel, jazz, and blues from the core curriculum, we risk graduating singers who can sing notes without understanding context. That is artistry without integrity. Consider the Civil Rights Movement: songs like “We Shall Overcome” and “Oh Freedom” weren’t just spiritual testimony; they were political weapons, shaping protest and inspiring solidarity. Teaching contemporary music without teaching these traditions deprives students of understanding how music moves societies.

This is the crossroads facing music schools across the United States. Once, the unquestioned core was Western classical music. Today, ethnomusicology teaches us there is no universal foundation - there are many foundations, each grounded in cultural context [Nettl, 2005]. Elevating gospel, jazz, and blues is not about discarding Bach or Mozart. It’s about aligning curricula with reality: the sounds people hear daily, the genres students aspire to perform, and the industries they dream of entering.

At every stage of my musical life, I learned that the world lives inside the music. History, politics, religion, science, and art live in every note. That’s why gospel, jazz, and blues are not electives. They are the origins of the American voice, and of countless individual voices. Curricular decisions are not mere scheduling details. They are cultural decisions - decisions about whose stories we preserve and whose we forget. When gospel, blues, and jazz are electives, we tacitly approve of forgetting. When they are required, we transmit truth and integrity. James Baldwin captured it long ago: “It is only in his music… that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story.” If that story is treated as optional, we betray the music and the musician.

This is why I call this blog The Sacred Voice. Our voices carry histories that must be learned, taught, and embodied. My challenge to you is simple: take one song you love, any American pop anthem. Listen to it intently. Notice how gospel, jazz, and blues live within the voice and tones. Let that awareness remind you that your own voice is part of something larger. Additionally, if you’d like a practice: sing one line from that song out loud. Pay attention to where your breath catches, where your pitch opens, and where your phrasing bends. Then write in your journal for five minutes about what you noticed. Where do gospel, jazz, or blues resonate in your own sound?

The beauty of these traditions is that you’re never alone when you sing their songs. They carry the memory of communities, struggles, and triumphs that had an international and intergenerational impact. They are sacred precisely because they hold truth.

With love + vitality,

Shauna <3